Rethinking the Bank of Mum and Dad and mortgages

Read our think piece about whether the Bank of Mum and Dad can shake off its bad reputation and what options there are for parental support on mortgages.

The phrase “the Bank of Mum and Dad” is thrown around a lot - usually with negative connotations. In popular culture, it’s often represented by demanding, lazy children and their resentful, yet compliant parents. A 2004 TV show called “The Bank of Mum and Dad” centered on wayward adult children learning how to spend frugally with advice from their parents.

When you type “The Bank of Mum and Dad” into Google, you don’t see reference to the short lived early noughties TV show. Instead there are pages and pages of results about first-time buyers using parental support to get onto the property ladder. It’s true that the Bank of Mum and Dad is a vital support. One of our reports showed that at least half of first-time buyers used help from their parents to buy their first home - but why is there such a taboo around parental support? Can (and should) the Bank of Mum and Dad mortgages shake off its bad reputation?

The American Dream myth

Buying a home is arguably the most important and personal financial decision of your life. As such, we thought it would be a good idea to get a personal opinion on it. Eve, who is 27, has been renting in London for the past 6 years, all the while trying to save a house deposit. In a bid to save faster, she and her boyfriend have moved into a two-bed rental with a housemate to reduce their monthly rent.

When asked whether she would be willing to get help from her parents to buy a home, Eve’s take was that she wanted to go it alone. Stoic as that might be, it’s an interesting and headstrong thing to say - and potentially misinformed.

Eve seems to have adopted the philosophy of the American Dream; work hard, and you can achieve anything. An influencer and ex-Love Islander recently caused uproar by sharing her view in an interview that we all have the same 24-hours, and that her monumental success was the result of hard work and hard work alone.

“She’s being ignorant!”, “She’s privileged!” people cried, “not everyone has the same opportunity, it’s not hard work holding people back from her lifestyle, it’s lack of access!”. But are we so quick to rush to the defence of other inequalities? Let’s look at housing.

Then vs now

Eve’s parents got on the property ladder in 1993, purchasing a one bed flat in Fulham for £63,000. They had no financial support from their families. That same property is now worth over £500,000. In today’s market, the flat would require a minimum £50,000 deposit and a household income of £100,000. Out of reach for Eve and her partner. But, does that make them lazy? Have they spent their money waywardly? Or, like many first-time buyers, are they unlucky in circumstance. Judging by the number of weekends and evenings Eve works, we can assume it’s the latter.

Eve’s parent’s situation is not unique. There has been a 227% increase in house prices since the 1970s. Paired with wage stagnation and the increasing cost of renting, the result is that there are fewer first-time buyers than ever before.

That isn’t to say that Eve’s parent’s generation had it easy. Interest rates were at 15% in the years before they bought their first home. But it is undeniable that the barriers they faced to homeownership were smaller than they are for young adults today. Let’s look at a few comparisons:

- A single adult in 2020 earned an average salary of £31,487. In 1999, the average salary was £17,803, but taking into account inflation, this looks more like £31,428. So, despite inflation of 77%, salaries increased by a mere 0.2%.

- In 2020, average house prices stood at a record high of £252,000. At the end of 1999, that number was £91,199. Taking into account inflation, that’s around £160,998 in today’s money. So in 1999, the average house price was just over 5x average income. In 2020, it was over 8x income.

These comparisons are two a penny, but where does this leave the conundrum of the Bank of Mum and Dad. How do these comparisons affect the public’s opinion?

The Bank of Mum and Dad taboo

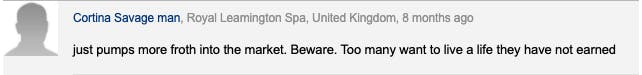

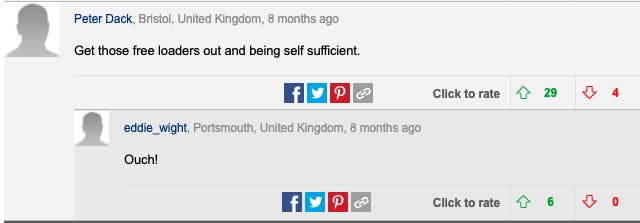

For Tembo’s launch, we featured in a Thisismoney article which focused on case studies of a few Tembo customers who used a family Boost mortgage to buy their first home. It was met with some ferocity in the comments section.

The statement: “too many want to live a life they have not earned” is particularly interesting. Homeownership offers security, freedom, and the ability to invest in your future. At what point does someone earn a chance at homeownership? Do they have to be working a 70 hour week? Do they have to work in banking? This concept of young people not working hard enough to buy plays into the perception that those that use the Bank of Mum and Dad are freeloaders. It puts the emphasis on the individual, and entirely denies the market forces at play.

Not all Bank of Mum and Dad taboos are aimed at younger people. An assumption is generally made that family support is only available to the very wealthiest of families. So the rich get richer and the rest of us watch from the sidelines. But with half of first-time buyers using their parents to buy a home, it’s clearly not a luxury for the 1%.

Why we need the Bank of Mum and Dad mortgages

Within society, we attempt to redress wealth disparities in all sorts of ways. We pay tax so that those who have fallen on hard times can be supported. We give a few spare coins to someone living rough. If someone has struggled in their life compared to another, it is more likely than not down to the fact that they have not been offered the same opportunities. No 24-hours are the same.

Generational wealth equality is no different. With the vast majority of wealth owned by the over 50’s, a natural redress is needed, and in the absence of significant government support - families are taking it into their own hands.

One of the most basic instincts a person has is to protect their family unit. Back in the day, this might have consisted of fending off predators, or teaching your kids which plants were poisonous. But today it’s setting up a savings account for your child when they are young, or unlocking money from your own property to gift to your child. A natural goodwill and empathy is resulting in a trickle down of wealth from older generations to their children and grandchildren.

But to be a true force for good in society, the Bank of Mum and Dad needs to be more accessible. Not all families have access to a cash lump sum of the size needed to help with a deposit these days. But if we open up new ways of redistributing wealth, through sharing a cut of the equity that has built up in a parent’s home, or allocating some of their income to their child’s mortgage, the Bank of Mum and Dad can help a wider group of people.

Approach with nuance

Clearly this topic requires nuance. Generational differences shouldn’t eliminate individual successes, and they certainly don’t make older generations ‘lucky’ or younger generations ‘scroungers’. While older generations are more likely to have larger sums of capital, there are still large disparities in wealth amongst Boomers. Equally, while it’s harder to get on the property ladder now, just over 10% of 25-35 year olds own a home.

It’s also unavoidable that not all buyers will have access to the Bank of Mum and Dad, no matter how many new pathways to redistributing wealth there are. Meaningful support from the government and other private innovation will remain important. But it is a viable way for families to create equal opportunity within their family unit. It’s certainly not a dirty word, or something to be ashamed of.

So, it’s time we viewed the Bank of Mum and Dad in a different light - one that takes into account generational inequality, the notion that families want to look after each other, and how economic factors outside of the individual’s control are at play. No amount of ‘hard work’ can magic up a miracle for today’s would-be buyers, but family support can provide an answer.